Understanding Acute Grief and Trauma Part 2: Why Grief Can Feel Overwhelming, Unreal, or Numbing

In Part 1, we explored how the brain and nervous system are designed for survival, efficiency, and rapid threat detection. In this section, we’ll look more closely at what actually happens in the body during acute grief—and why certain reactions can feel sudden, intense, or disorienting.

Why Grief Reactions Can Feel So Intense

Lower brain structures act much faster than higher, thinking parts of the brain. They are designed to respond immediately to danger, not to reflect or analyze. Because of this, their reactions are often more extreme, more physical, and less verbal.

One of the most important structures involved in acute grief is the amygdala.

The Amygdala: The Alarm That Won’t Wait

The amygdala stores emotional and bodily memories, especially those connected to danger and loss. It works through implicit memory, meaning it doesn’t rely on words or conscious recall. Instead, it responds to sensations, images, sounds, and internal body states.

When acute grief activates the amygdala:

the brain reacts before you can think,

the body shifts rapidly into survival mode,

emotions and sensations can feel overwhelming or disconnected,

logic and reassurance often feel inaccessible.

This is why grief cannot be “talked away” in its earliest phases. The part of the brain in charge is not interested in reasoning—it is focused on survival.

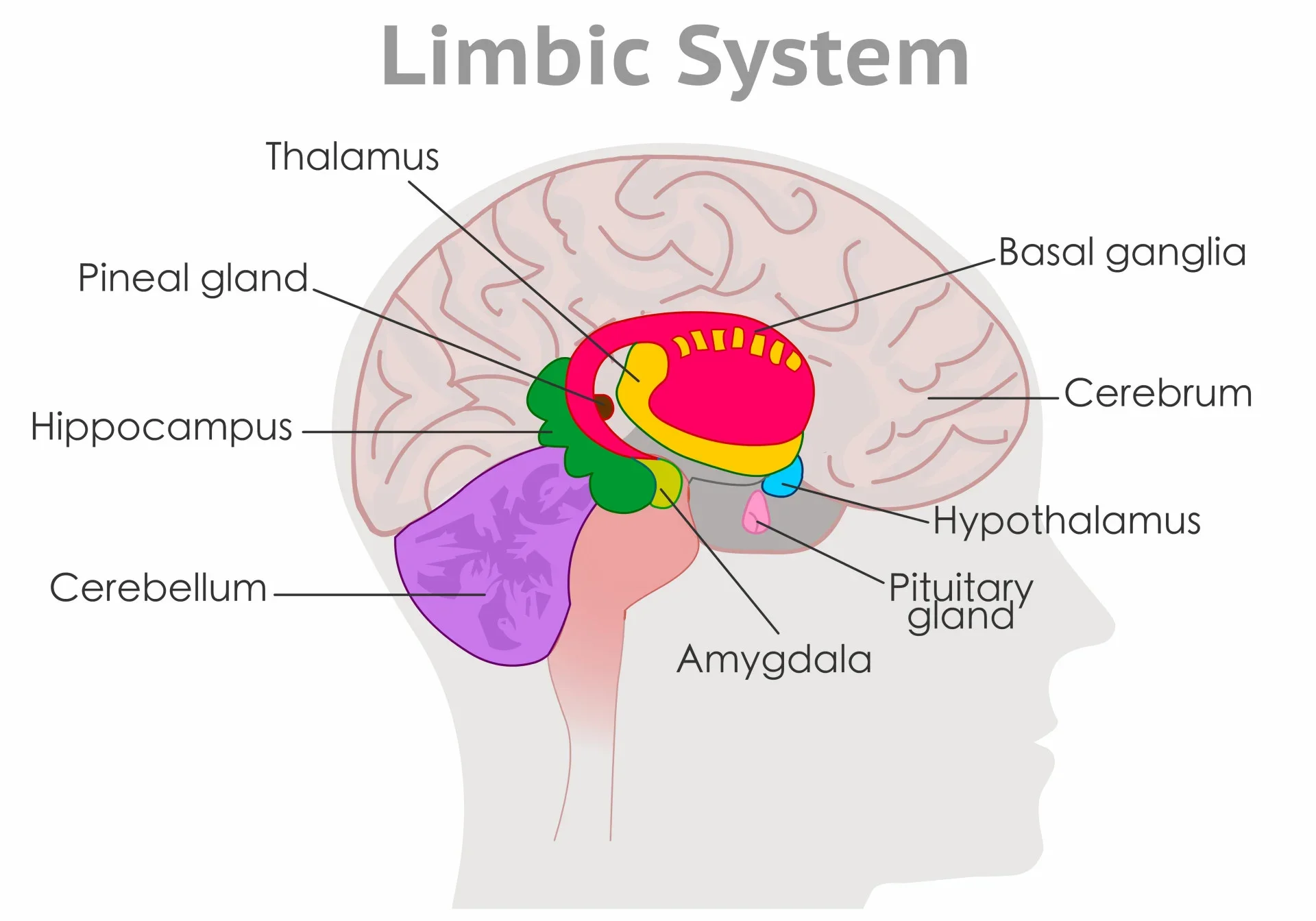

Chart of the Limbic System

The Nervous System

Grief can strongly activates the autonomic nervous system, which has multiple pathways for dealing with perceived threat and safety.

Ventral Vagal: Safety and Connection

The ventral vagal system supports feelings of safety, calm, and social engagement. When this system is active:

the body feels settled,

breathing is steady,

digestion is active,

emotional presence feels possible.

This is the state you experience when you’re sharing a meal with people you trust, sitting comfortably in your home, or feeling at ease without needing to stay alert. Some forms of light, everyday dissociation—daydreaming, zoning out while driving, soft emotional distance—occur here and are normal, adaptive, and healthy.

Sympathetic: Mobilization and Alarm

Although not your primary focus here, it helps to know that sympathetic activation shows up as:

anxiety

agitation

racing thoughts

restlessness

panic or irritability

Many grievers move rapidly between this state and collapse.

Dorsal Vagal: Shutdown and Disconnection

The dorsal vagal system emerges when threat feels overwhelming and escape or action feels impossible. This is a deep metabolic shutdown response. It can look like:

emotional numbness

feeling detached from reality

time slowing or stopping

body heaviness

inability to speak or respond

feeling unreal or outside your body

A classic example is the shock following a car accident—looking around and feeling like nothing is real, or staring at your hands and feeling as if they don’t belong to you.

In grief, dorsal vagal states are extremely common in the early stages. The loss is simply too much for the system to process all at once, and shutdown becomes protective.

For most people, this state is temporary and gradually gives way to other emotions—sadness, longing, anger, yearning—over time.

When Grief Overwhelms the System

The question becomes:

What happens when grief is so overwhelming that the nervous system doesn’t fully come back online?

This is where dissociation becomes important to understand.

Dissociation: When the System Protects by Disconnecting

Dissociation is not a character flaw or weakness. It is a biological survival response. At its core, dissociation alters perception in order to reduce suffering.

However, when dissociation becomes rigid and long-lasting, it can interfere with healing.

Pathological dissociation is most often associated with:

early relational trauma,

repeated or prolonged trauma,

or severe, unprocessed acute grief.

Neurobiologically, it reflects a closed, highly defensive right-brain system, where:

emotional experience becomes flattened or inaccessible,

the world feels less meaningful,

relationships feel distant or unreal,

the body and mind feel disconnected.

In these states, there is a breakdown between:

higher and lower brain regions,

emotional and cognitive processing,

the brain and the autonomic nervous system.

This collapse affects both subjective experience (how you feel inside yourself) and intersubjective experience (how you connect with others).

Why Chronic Dissociation Interferes With Healing

Long-term dissociation limits opportunities for relational learning—the experiences that teach the nervous system that connection can be safe again.

Healing after loss often requires:

tolerating emotion in small doses,

experiencing being understood,

feeling held in relationship,

allowing new meaning to form.

When dissociation dominates, the system avoids these experiences entirely—not because it doesn’t want connection, but because it has learned that connection feels too dangerous or overwhelming.

This is why grief sometimes feels “stuck.” The nervous system is still protecting, even when the danger has passed.

Grief Responses Are Not Failures—They Are Adaptations

Every grief response discussed here developed for one reason: to help you survive overwhelming loss.

Nothing has “gone wrong” if you feel numb, detached, flooded, or confused. These states are signs that your brain and body have been working overtime to protect you during profound pain.

The work of grief is not to force these responses away—but to slowly, safely help the system learn that it is possible to feel again without being destroyed by the loss.

Coming Next: What Trauma Really Is

In Part 3, we’ll explore:

what trauma actually means in neurobiological terms,

the development and basics of EMDR

and how this knowledge shapes effective treatment.

Understanding trauma at the nervous-system level allows us to approach healing with compassion, precision, and patience—rather than self-blame or pressure to “move on.”